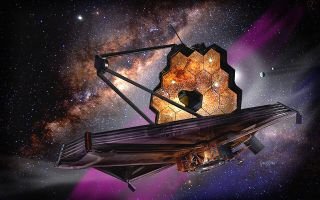

In this excerpt from “Pillars of Creation: How the James Webb Telescope Unlocked the Secrets of the Cosmos” (Little, Brown Book Group, 2024), author Richard Panek looks at the staggering story behind the JWST’s launch — and how it nearly fell apart at the final hurdle.

“If they’re going to cancel, it doesn’t matter,” Mike Menzel would tell his crew in the years to come. “Don’t worry. Don’t even listen.”

On a fairly regular basis, Menzel had to appear before a review board — the practice that his longtime Hubble telescope partner and Webb collaborator Peter Stockman once compared to kabuki theater — to explain why the project was taking so long or costing so much. His answer was almost identical to what he had said when Frank Martin showed him the observatory plans at Lockheed Martin in the late 1990s:

Relying on analysis — completing one mathematical model for the part of the satellite on one side of the sun protection, then completing another mathematical model for the part on the other side of the sun protection, and then seeing if the models could match — was far more prone to human error than simply putting the whole kit and caboodle into a chamber with several floors and shaking it like there was no tomorrow (which, in the event of stress-test failures, might not be the case in terms of the mission’s future).

What they needed, Menzel told the review boards, was “margin” — an abbreviation for not just margin of error but margin of error beyond the margin of error. “Normal rules don’t apply here,” Menzel liked to say. “This is a virgin territory” — a landscape of predictable challenges but, more important for his purposes, unpredictable dangers as well. “Unknown unknowns,” as the Webb crew called problems they couldn’t imagine.

“How much margin do you need?” one or the other program manager would ask Menzel from time to time.

“As much as I can get,” he would reply.

Budget overruns, bureaucratic bungling, congressional oversights, review-board calculations, the whole process of rethinking how to test a space telescope: Webb had survived them all. Another factor, however, continued to play havoc with the budget and launch timeline well into the 2010s—what Menzel called “stupid mistakes.”

One such mistake was incorrect wiring that burned out some of the prototype’s electrical components—for example, the pressure transducer for the propellant (the transducer is, more or less, a gas gauge). Could we fly without the pressure transducer? Menzel’s team had to debate the question. The verdict: no. So they had to replace them.

Another silly mistake: the use of an unsuitable solvent that damaged the observatory’s propulsion valve.

And another: seven cracks in the sunshield.

Another: a vibration test for the sunshield that ended with dozens of bolts coming loose and bouncing around the test chamber. The problem turned out to be that the bolts had too few threads. (Team members spent months retrieving bolts from far-flung corners of the facility.)

Partly because of these mishaps, the launch date slipped from October 2018 to June 2019. After investigating the delay, the U.S. Government Accountability Office released an analysis warning that even a June 2019 launch date was too optimistic, and exactly one month after the Accountability Office released that analysis, NASA announced another delay, to spring 2020. It also acknowledged that Webb had reached Congress’ $8-billion-or-bust budget limit … and would have to exceed it if the telescope was ever to get off the ground.

In January 2019 Congress approved an additional $800 million investment, bringing the total expenditure to $8.8 billion. An accompanying report was brutal. “NASA and its contractors are deeply disappointed in the mismanagement, lack of careful oversight, and overall poor basic workmanship on JWST,” the report said.

“NASA and its commercial partners believe that the funding provided by Congress for this project and other development efforts is an entitlement, unaffected by failures to stay on time or within budget.” And once again Congress threatened the project’s survival: “NASA must strictly adhere to this limit or, under this agreement, JWST will have to make cost savings or cancel the mission.”

“Just forget about them,” Menzel told his team. “I don’t care what they say. If you see a problem, just say so, and if we have to delay, we’ll delay.”

He compared the final preparations for the launch to folding a parachute: “One little mistake and we’re dead.” Then came COVID, and with it a slowdown in work, leading to the announcement in July 2020 that the telescope would not launch before Oct. 31, 2021.

For two years, Webb’s components had been coming together at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory, just outside Pasadena.